I

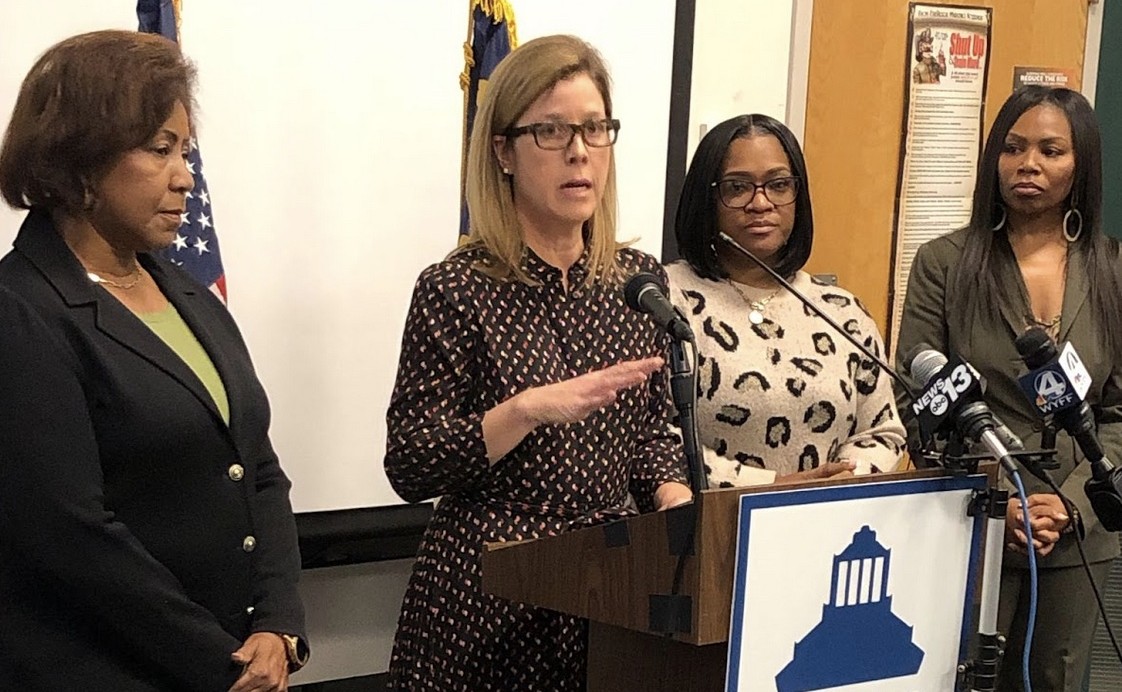

n Asheville, a mayor who votes “yes” on a development project often faces backlash. Mayor Esther Manheimer, first elected to City Council in 2009 and to the mayor’s office in 2013, has been repeatedly accused of favoring developers—a claim that circulates on social media and is amplified by snarky comments that ignore the council’s seven‑member decision‑making body. The question arises: does her background as a real‑estate attorney create a conflict that disqualifies her from serving?

Asheville operates under a council‑manager system. The six‑member City Council sets policy; the city manager implements it. The mayor, chosen on a separate ballot, presides over council meetings and serves as the ceremonial head but also votes on issues. When a conflict exists, the mayor can recuse herself. Manheimer has recused on a handful of occasions, a fact confirmed by City Attorney Brad Branham, who recalls only three or four instances in seven years. State law, specifically General Statute 160A‑75, requires elected officials to vote unless a clear conflict exists.

Manheimer’s legal practice, based at Van Winkle Law Firm, covers title insurance, easement and boundary disputes, homeowners associations, and other real‑estate matters across western North Carolina. She notes that while a firm attorney may represent a developer, she herself recuses when necessary. The firm’s former attorney, who handled many development cases, left in 2023, reducing potential conflicts.

A recent conflict surfaced with a proposed 36‑unit development on Springside Road. The project required conditional zoning; neighbors opposed it due to traffic and safety concerns. The developer, Sage Communities, had a site photo submitted to the Planning Department. Some neighbors, led by Kendra Miller, sought a meeting with Mayor Manheimer before the council vote. Because Manheimer’s firm had ties to parties involved in title and development disputes, it was unclear whether she could vote. Miller, a nutritionist and concerned resident, expressed frustration at the late opportunity to meet. The mayor’s assistant was helpful, but the mayor’s dual roles left limited time.

The council ultimately approved the rezoning 5‑2. Branham cleared Manheimer to vote, and she cast a yes. Miller acknowledged that while conflicts can hinder city progress, they are not disqualifying; they stem from firm associations, not her own representation. Branham agreed, noting that in a city the size of Asheville, few attorneys handle development, making some overlap unavoidable. In the Springside case, two firm attorneys were involved—one had ceased representation, the other had handled probate work for a party in the matter. Due diligence was required, and Manheimer was placed on hold until four days before the rezoning vote.

North Carolina’s conflict statutes are clear. GS 160A‑75 obliges officials to vote unless a statutory conflict exists. GS 160d‑109 bars voting on rezoning or development regulation when a close relationship with the landowner or applicant exists. GS 14‑234 prohibits officials from approving contracts that benefit themselves. These laws aim to prevent officials from exploiting their positions while ensuring they participate in governance.

Some argue that a strong‑mayor system—where the mayor is a full‑time professional—could reduce conflicts. Political scientist Chris Cooper counters that a lawyer’s occupation does not disqualify them; many public servants are lawyers. Restricting lawyers would limit the pool of candidates. Cooper notes that strong‑mayor systems have historically led to corruption (e.g., Chicago’s Daley, New York’s Tweed) and that Asheville’s council‑manager model, with a trained city manager, aligns professional governance with public expectations. While a full‑time mayor could focus solely on city affairs, they might still maintain a private practice, perpetuating potential conflicts.

In practice, Manheimer’s recusal record is minimal, and her conflicts are largely firm‑based rather than personal. She has complied with legal requirements and maintained transparency. The broader issue remains Asheville’s rapid development and the tension between growth and community concerns. Local governments cannot unilaterally veto projects without risking litigation from developers and their attorneys.

Asheville Watchdog invites readers to discuss these matters on its Facebook page. The nonprofit news organization, led by John Boyle, continues to cover local issues. For support, visit avlwatchdog.org/support-our-publication.