M

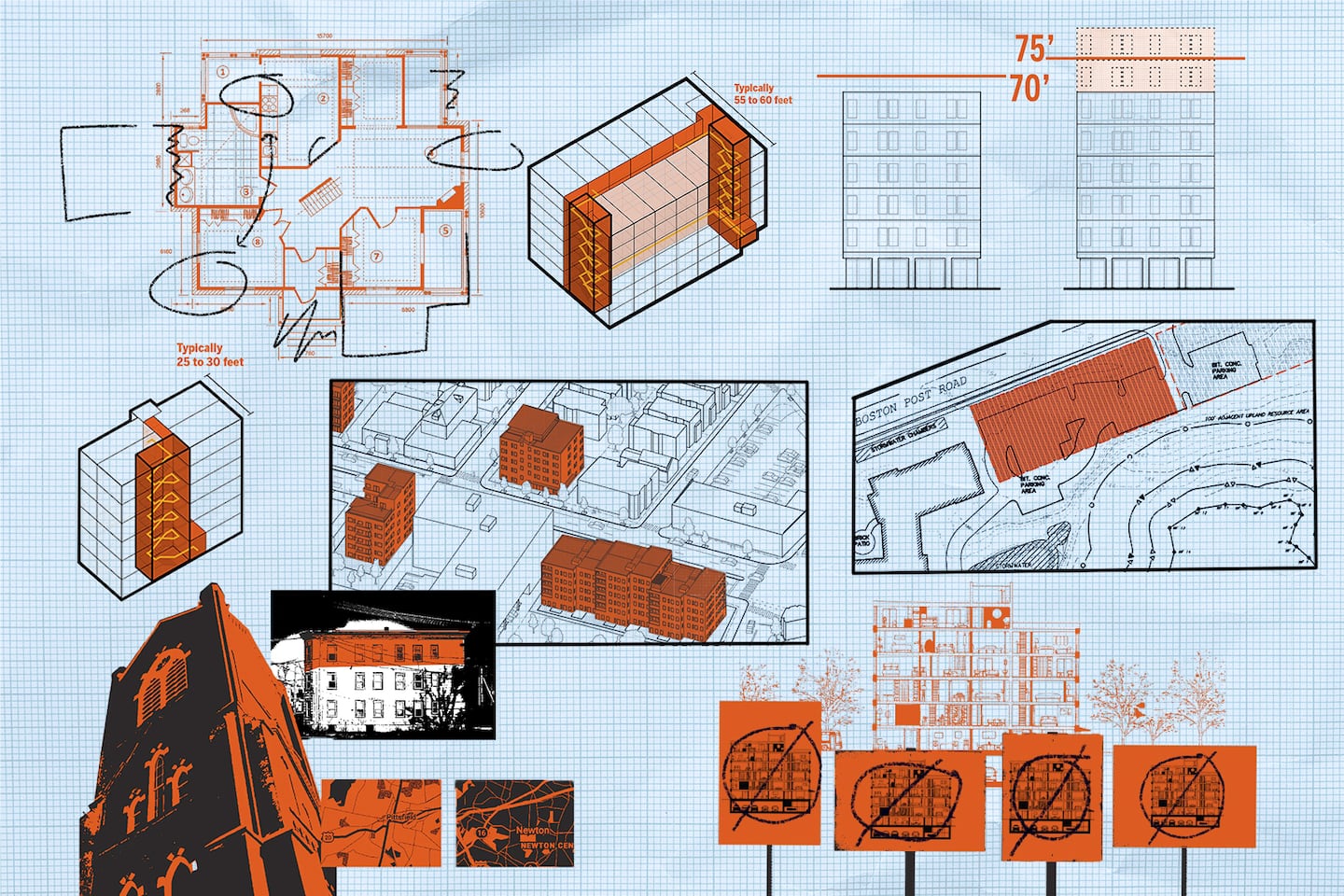

unicipalities should appoint “development advocates” to work side‑by‑side with housing developers, turning the current adversarial climate into a collaborative, win‑win process. As a retired architect, developer, and long‑time housing advocate, I’ve seen how zoning rules and local planning departments often tilt the deck against both for‑profit and non‑profit builders. By assigning staff who can negotiate, assess economic feasibility, and redesign projects to address community concerns—such as sunlight, views, or traffic—municipalities can help projects grow to the right size without harming neighborhoods.

In Massachusetts, even cities that have relaxed zoning, like Cambridge, still lag in permitting new homes. Cambridge has eliminated parking mandates, cut setbacks, and raised density limits while offering incentives for affordable units. Yet, over the past five years, the number of new housing units has fallen sharply. Rising construction and financing costs mean developers cannot recoup expenses, especially when affordable housing projects require subsidies. A recent lawsuit by a Cambridge developer challenges the city’s inclusionary zoning, a policy designed to spur affordable construction.

The cost of building an affordable unit now averages $900,000. To make such projects viable, municipalities, state agencies, and private partners must provide tax credits, low‑interest loans, and public‑private partnerships. First, local governments need to identify unmet housing needs; then they can deploy financial tools to turn zoning reforms into tangible units.

Despite decades of advocacy—from the Community Preservation Act to zoning reform working groups—progress remains limited. Many residents publicly endorse affordable housing but resist it in their own neighborhoods. Massachusetts, a home‑rule state with 351 municipalities, has struggled to translate state‑level successes—Chapter 40B, the MBTA Communities Act, and the Affordable Homes Act—into local action. Professional associations, non‑profits, and government agencies have pushed for change, yet the “moral imperative” to increase affordability has had little effect on many towns.

The key to overcoming this impasse lies in engaging local communities directly. By involving residents in the planning process, addressing their legitimate concerns, and demonstrating how new housing can benefit the broader area—through job creation, increased tax revenue, and improved services—municipalities can build broader support. Development advocates can bridge the gap between developers and residents, ensuring that projects meet economic realities while respecting community character.

In short, a coordinated approach that blends relaxed zoning, targeted financial incentives, and proactive community engagement—facilitated by dedicated development advocates—offers the best path forward for expanding affordable housing in Massachusetts.