I

n 2011, Texas received only 14.7 inches of rain, sparking fears that a water shortage could stall the state’s growth. Subsequent years delivered more typical precipitation, easing those concerns. When rainfall meets acceptable levels, worries about water availability quickly subside. Historically, droughts have driven Texans to scrutinize water policy, viewing scarcity as a threat to long‑term prosperity. Yet Texas has long been a pioneer in forward‑looking water planning.

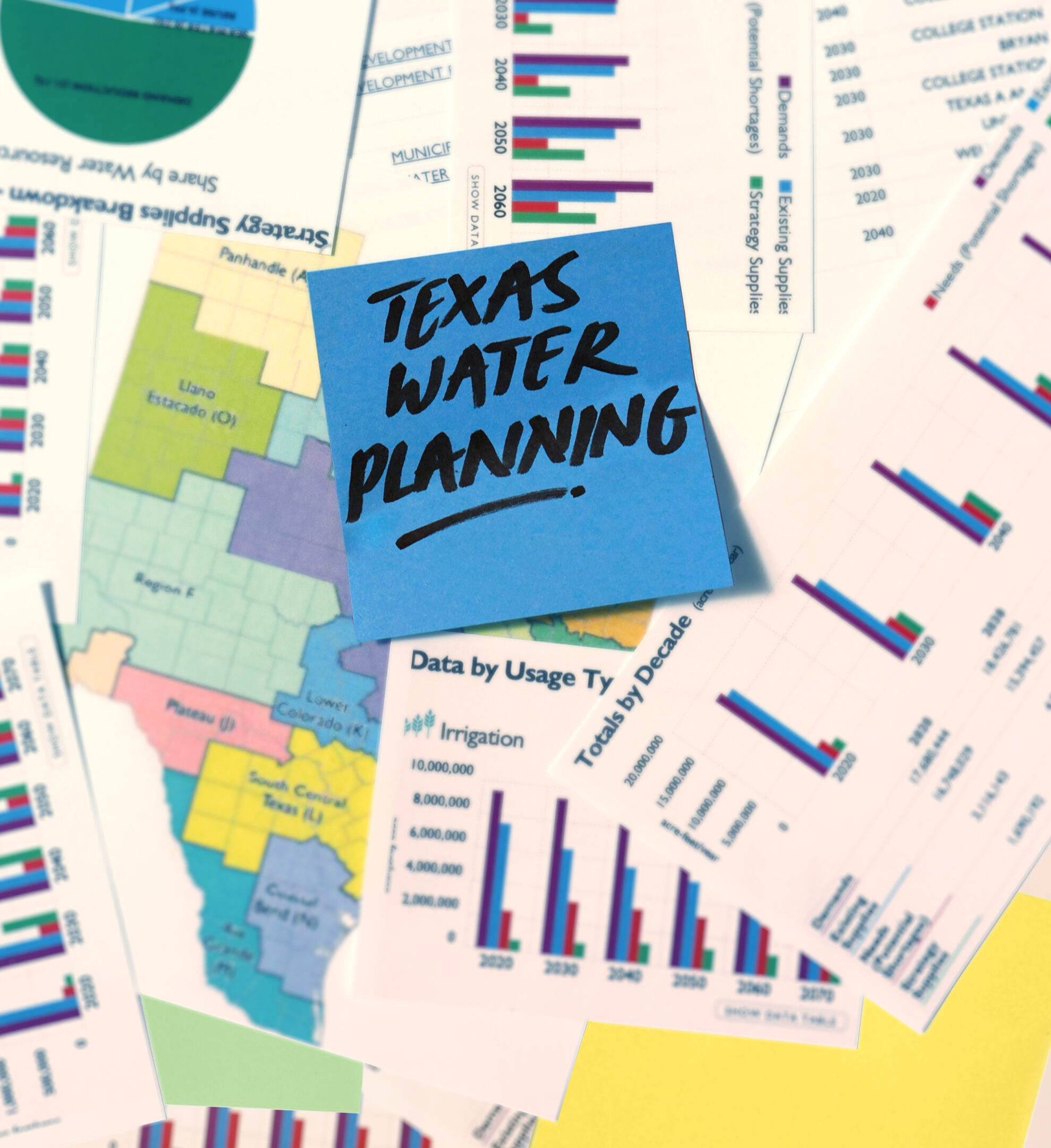

**Why Texas Tracks Its Water Supply**

Texas’s water‑planning tradition began with severe droughts. The 1917 dry spell produced just 14.06 inches—well below the 1895‑2019 average of 26.79 inches—making it the driest year in that span. The agricultural devastation prompted the state to add Article 16, Section 59 to its Constitution, declaring the preservation and conservation of natural resources a public duty. This empowered the legislature to enact measures for water conservation, leading to the creation of river authorities and reclamation districts and marking the start of statewide water plans.

The 1950s drought, especially 1957’s 14.98 inches, was the third driest year on record. The 2011 total of 14.7 inches surpassed 1957, making it the second driest year. Because every year from 1950 to 1957 fell below the long‑term average, planners treated that period as the drought of record. In response, the legislature established the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) to plan and finance water supply projects.

**Regional Water Planning Groups**

In 1961, TWDB released the first state water plan. The 1980s added long‑term supply‑and‑demand forecasting. A milder 1996 drought prompted Senate Bill 1 in 1997, creating a bottom‑up planning process centered on 16 regional water planning groups. These groups, composed of local stakeholders, reflect Texas’s demographic, economic, geological, and climatic diversity. Each group plans for a decade‑long “drought of record” over the next 50 years, projecting demand from population growth and supply from existing sources adjusted for future changes such as aquifer depletion. The shortfall between projected supply and demand defines the group’s “needs,” which they address with strategies that often require substantial capital investment. Typical groups have about 20 voting members representing agriculture, industry, environment, municipalities, water districts, river authorities, utilities, counties, groundwater districts, and power generation.

**Water Supply and Demand**

Every five years, TWDB approves each regional plan and consolidates them into the state water plan. The tenth plan, released in 2022, projects that Texas will fail to meet all users’ needs during a record drought. By the 2040s, recommended strategies should cover all demands, though some users—particularly in irrigation, steam electric power, livestock, and mining—will still face shortfalls. The plan’s projections hinge on implementing the envisioned supply strategies, which derive 46 % of savings from demand reduction (mostly conservation) and 48.7 % from adding reservoirs, drilling wells, and reusing supplies; desalination contributes a mere 0.2 %.

**What Happens Without Action?**

The plan forecasts a 73 % population increase by 2070, with most growth in Regions C (Dallas‑Fort Worth) and H (Houston). Urban water use would surpass irrigation, the current leader. Existing supplies are projected to decline from 16.8 to 13.8 million acre‑feet per year, creating a 6.9 million acre‑feet per year shortfall by 2070 during a repeat of the record drought. The plan proposes 5,800 strategies, requiring 2,400 projects at an estimated $80 billion cost to add 7.7 million acre‑feet per year by 2070. Failure to implement these strategies would leave nearly 25 % of Texans with only half the municipal water they need in 2070, inflicting $153 billion in economic damages.

**Funding Water Infrastructure**

The State Water Implementation Fund for Texas (SWIFT) was created in 2013 via Proposition 6, transferring $2 billion from the Economic Stabilization Fund to SWIFT. SWIFT offers low‑interest loans and other assistance for projects identified in the state water plan.

In 2023, Governor Greg Abbott signed several water‑related bills, including SB 28, SB 30, and Senate Joint Resolution 75, establishing the Texas Water Fund (TWF) and authorizing a one‑time $1 billion supplemental appropriation. However, Jeremy Mazur of Texas 2036 testified that this amount falls far short of the nearly $154 billion needed to address aging infrastructure and diversify supply. Texas 2036, part of the Texas Water Fund Coalition, advocates for long‑term investment in water infrastructure.

The legislature also passed House Joint Resolution 7 (HJR 7), allocating $1 billion annually from 2027 to 2047 (total $20 billion) to secure the state’s water supply. This funding will support both repair of aging systems and development of new sources, including desalination and wastewater treatment. Governor Abbott signed SB 7, the “generational investment in water” bill, which assigns the TWDB responsibility for coordinating water supply conveyance and expands the New Water Supply for Texas Fund. The supplemental budget (HB 500) adds a one‑time $2.5 billion to the water fund, with $1.6 billion available for 2025‑27 projects.

**Who Is Responsible for Future Water Demands?**

Texas’s proactive, transparent planning process makes it a national leader. Every regional planning group holds public hearings and publishes agendas, inviting public participation. In addition to the TWDB, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), river authorities, utilities such as the San Antonio Water System (SAWS), and groundwater conservation districts contribute to the planning process. Academic and nonprofit partners—including the Texas Water Resources Institute at Texas A&M, the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas, and the Texas Water Foundation—also play key roles. Researchers Lynn D. Krebs, Ph.D., and Charles E. Gilliland, Ph.D., provide economic analysis to support decision‑making.