P

roperty insurance was originally intended to protect owners during hardship, but its generous terms may have helped drive urban decline. Economists Ingrid Gould Ellen, Daniel A. Hartley, Jeffrey Lin, and Wei You explored this paradox using late‑20th‑century U.S. residential data.

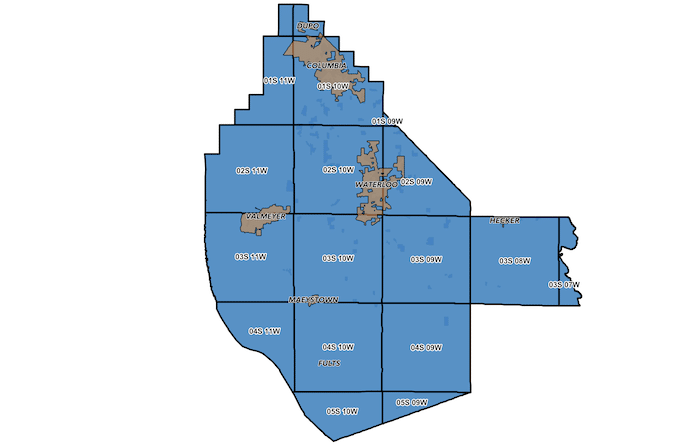

The study begins in the 1960s, when Congress launched a program to give low‑income families better access to affordable housing. A key element of that program was the Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR), designed to expand the supply of reasonably priced property insurance so landlords could offer lower rents. FAIR’s regulatory framework required insurers to share losses, prohibited consideration of environmental hazards, and mandated unusually generous payouts—often exceeding a property’s market value. By 1968, 18 states offered FAIR plans; by 1970, 26 states did, and the number of policies grew from 300,000 in 1969 to 5.7 million by 1977.

Under FAIR, underwriting standards collapsed. In Illinois, only 1 % of applicants were denied coverage. The resulting flood of policies, many of which would never have been issued otherwise, exposed insurers to heightened risk. Fraudulent claims proliferated; FAIR plans lost $1.5 billion between 1970 and 1998.

To assess neighborhood impacts, the authors compared 6,000 census tracts across 30,000 tract‑year observations from 1950 to 1990. After 1960, most central cities—whether or not they adopted FAIR—saw population loss and falling property values. Cities with early FAIR implementation experienced even steeper declines: by 1980, tracts in these cities had lost hundreds of homes, and income levels had dropped sharply. The data reveal a clear link between FAIR’s generous coverage and accelerated disinvestment, especially in areas where FAIR arrived by 1970.

The study also examined physical decay. Fire emerged as a major cause of damage, whether accidental, negligent, or arson. Nationwide fire data show that, after 1968, cities in early‑FAIR states experienced 32 % more building fires than non‑FAIR cities. The spike in fires coincided with a rise in abandoned properties, as landlords abandoned buildings to trigger insurance payouts that exceeded the structures’ worth. When neighborhoods deteriorated, a new class of real‑estate entrepreneurs—those willing to neglect and abandon properties—emerged, exploiting the over‑insurance incentive.

Policy reforms in the 1980s curtailed FAIR’s generosity, and fire incidents fell sharply thereafter. The authors caution that while FAIR’s intentions were noble, the program’s design unintentionally encouraged abandonment and fire damage, amplifying urban decline. Their findings suggest that insurance regulations can have unintended consequences, and that careful calibration is essential to avoid encouraging neglect of properties.

In sum, the research demonstrates how a well‑meaning policy—FAIR—can backfire when it removes underwriting discipline and offers payouts that outstrip property values. The resulting chain of events—abandonment, fires, and disinvestment—illustrates the complex interplay between insurance policy, housing markets, and neighborhood vitality. Policymakers, property owners, and residents can draw lessons from this case: even protective measures can destabilize communities if they undermine incentives for maintenance and responsible ownership.