F

. Murray Abraham stands beside a window, eyes fixed on the camera, a quiet portrait of a man whose life has unfolded across stage, screen, and the quiet corners of his Manhattan duplex. His wife of six decades, Kate Hannan Abraham, passed away three years ago after a long illness, leaving a silence that only the walls of their two‑bedroom home can echo.

“I didn’t want to change anything in our apartment,” Abraham says of the space that has been his sanctuary since 1965. “But our daughter kept saying, ‘You’ve got to do the house over.’ I suppose she thought it should be brought back to life. And she was right. But it was awhile before I could get to that point.”

The actor’s career has spanned Oscar‑winning drama, blockbuster films, and acclaimed television. He earned the Academy Award for Best Actor in 1985 for “Amadeus,” and later appeared in “Scarface,” “Mighty Aphrodite,” “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” and the Emmy‑nominated series “Homeland.” Most recently, he joined the second season of “The White Lotus,” a role that brought him back to the set in Sicily, where he forged a friendship with co‑star Michael Imperioli and Imperioli’s wife, interior designer Victoria.

“Let’s return your home to the time when everything was happy and everyone was in good health,” Victoria urged, echoing his daughter’s earlier plea. “It took me almost a year to convince him.” Eventually, Abraham agreed, sending his wife to renovate while he filmed in Latvia. He returned to a hotel while the work continued, finally moving back in September. The result—a refreshed floor, fresh paint, marble countertops, and a touch of Art Deco—left him satisfied, though the apartment still awaits final touches: shelves, pictures, and furniture to be chosen between his eight performances a week.

The Oscar, a part‑time resident of the maisonette, is more often seen on display at the bistro across the street, where Abraham’s love of seared foie gras and the genial owner have made him a regular. “I think you should share an Oscar,” he once joked, offering the statuette to a fellow patron.

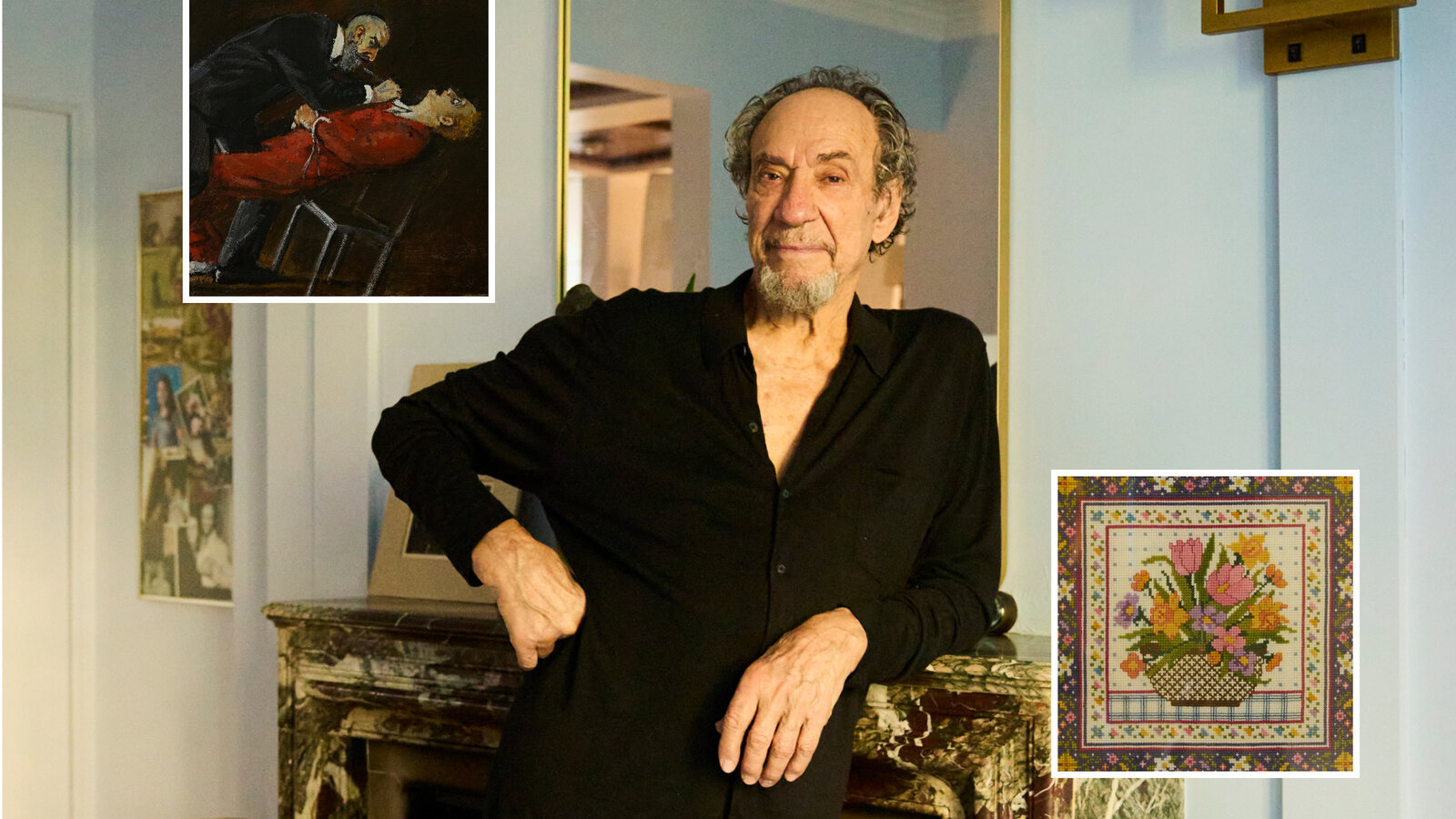

Kate’s creative spirit lives on in the apartment. She was a master of cross‑stitching and needlepoint, and many of her pieces adorn the weekend home upstate and the Manhattan loft. “She used to cue me on many of my scripts—she would have them memorized before I did—while we went over my lines,” Abraham recalls. “My granddaughter, Hannan, was raised in this apartment. I used to walk her to school. I loved the idea of charting her growth, and she was very excited about being stood up here and measured. And now she has suggested that we start measuring me because I’m shrinking.”

Abraham’s travels have left a tangible legacy in the exercise room and den. A prayer rug from Morocco, butterflies collected in Brazil, and a collection of Nabokov‑inspired specimens pay homage to his literary interests. “When I started making movies abroad I started bringing pieces back home and this is one of them,” he says of the Moroccan rug. “I got these butterflies in Brazil. At the time I was kind of in love with the literature of Nabokov, and I knew he was a lepidopterist. In tribute to him I started collecting butterflies.”

The couple’s move from Los Angeles to New York in 1965 brought them to a 52nd‑Street and 8th‑Avenue apartment just as the holiday season was winding down. “I like crowds, but my wife didn’t, so I walked to Times Square to look around and I picked up this,” he says, pointing to a well‑flattened horn that had been used for New Year’s Eve. Don Perlis, a painter and long‑time friend, has captured Abraham’s stage work on canvas for four decades, including a celebrated portrait of him as Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.” “That was my best performance,” Abraham says. “It was amazing, and I don’t say that about all my work.”

The bedroom is a study in golden velvet, with walls and bedspread matched in rich hue. Victoria transformed the space into a “man cave,” covering the walls in velvet and adding a sense of intimacy. “No one does that anymore but Victoria did it for me,” Abraham says. The small office on the ground floor once housed a collection of nude paintings by Perlis, which have since migrated to the apartment. “Don loves women, and I love women, too, and these are very good paintings by the way,” he remarks. Some of Perlis’s portraits of Abraham in various roles, including a depiction of him as Roy Cohn in “Angels in America,” now hang in the apartment, a nod to Kate’s grandmother’s crocheted hanger.

A graceful brown banister lines the staircase, capped with an ivory darning egg that once belonged to Kate’s grandmother—a tribute to family and craftsmanship. The apartment’s corner features a grandfather clock, a side table, and a lamp, while a brown couch sits in front of a window. Abraham’s admiration for Marlon Brando led him to attend the actor’s estate sale, where he met Brando’s son Christian and left with a haul of side tables, a bookcase, figurines, and lamps—one heavily dented, a souvenir of Brando’s own storied life.

Standing at his private entrance with the door slightly ajar, Abraham reflects on his vocation. “My work is my salvation and it’s been that way for my whole life,” he says, pausing to review lines for “The Queen of Versailles.” “Every actor will say the same thing: It’s torture when you’re not working. I’m 86, and I still have that same passion.”