A

fter two weeks, Lamarche reported that her client was freed from custody because of a mistaken identity, and the property sale went ahead thanks to the sellers’ willingness to extend the closing period.

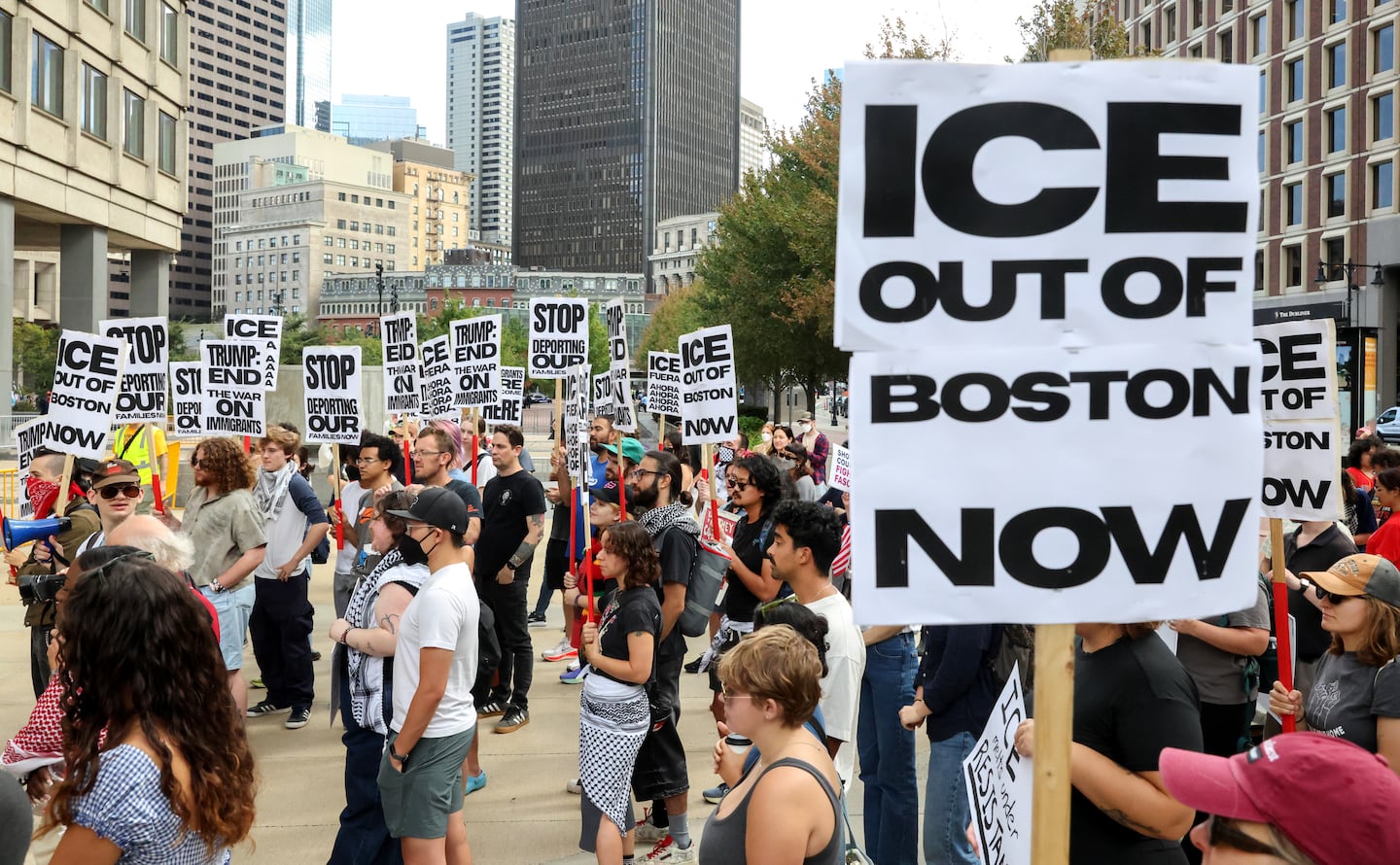

The recent sweeps have spread dread and confusion among people who fear ICE raids, disrupting their personal and professional lives regardless of their documentation status. While home ownership has long symbolized the American dream, many immigrants are now shelving those plans. Real‑estate agents and community advocates are offering advice to help clients safeguard their assets if ICE steps in.

“They’ve told me they’re putting a hold on buying,” Lamarche said of some clients. “Even those with legal status are scared to step out.”

Clients worry that routine steps—like pulling a credit report or writing a gift letter for a down payment—might draw attention. Lamarche also warned of broader economic fallout: stalled construction projects and higher prices due to a shrinking labor pool. Renters are becoming cautious, said Peggy Pratt, a Century 21 leader in Revere, NAHREP board member, and landlord. “The rental market has dipped,” she noted. Two tenants were detained by ICE last month. “People aren’t moving or spending on non‑essential things. They’re uncertain about what will happen.”

Landlords across Boston are reporting more vacancies. Pratt, who usually serves East Boston, Chelsea, and Revere, now receives calls from Everett, Malden, and other cities struggling to fill units that have been on the market since July—an abnormal duration. “They’re desperate,” she said. “We normally rent everything out in 30 to 60 days.”

She also hears homeowners selling and returning to their home countries to avoid ICE. Triple‑decker buyers are hesitant, fearing they won’t find renters.

In 2023, Latino homeownership in Massachusetts more than doubled over the past decade, according to the Massachusetts Taxpayers’ Foundation. The Urban Institute projects Hispanic households in the state to grow over 36 % between 2020 and 2030, and to account for more than 70 % of home‑ownership gains through 2040. Yet real‑estate professionals warn that a mass exit of Hispanic buyers could cripple the market. “If Hispanic buyers leave en masse, it will hurt the entire real‑estate sector,” Lamarche warned. “It could be catastrophic.”

In May, the Trump administration barred non‑permanent residents from qualifying for FHA loans—even those with work authorization. FHA loans, backed by the federal government, often offer lower rates and smaller down payments, appealing to first‑time buyers. “In Boston, buyers need to stretch every dollar,” Lamarche said. “The new restrictions push them further from the American dream of home ownership.”

The immigrant community drives much of the demand for affordable homes, said Bruce Marks, CEO of Boston’s Neighborhood Assistance Corporation of America (NACA). At NACA’s “Achieve the Dream” events—introducing buyers to education and mortgage programs—attendance has fallen because people fear ICE targeting public gatherings, especially those that attract immigrants regardless of status. NACA has received many questions about what happens if ICE raids an event.

A Social Security number isn’t required for a mortgage application; some applicants use an ITIN (Individual Taxpayer Identification Number) to file taxes. In April, the IRS and ICE agreed to share data, allowing tax information to be used for immigration enforcement. Three lawsuits, including one by Greater Boston Legal Services (GBLS) and a coalition of taxpayer and immigrant‑rights advocates, claim the agreement violates privacy protections among the IRS, ICE, and the Social Security Administration.

Marks noted that ITIN borrowers, even when facing deportation risk, have historically made payments diligently, expecting privacy. ITIN filings represented only 5,000–6,000 in 2023, according to the Urban Institute. “Intimidation and, in some cases, terrorizing the immigrant community significantly reduces demand for affordable home ownership,” he said.

Luz Arevalo, a GBLS attorney and tax clinic co‑director, is a plaintiff in the privacy suit. “People think filing taxes guarantees safety from immigration action, but that’s false,” she said. Angela Divaris, another GBLS attorney, argues that obtaining a Social Security number has become harder since the 1990s and that pushing people underground hurts tax collection. “We’re biting our own nose,” she said.

Arevalo added that many undocumented immigrants are integral to communities, owning businesses, homes, and having college‑educated children. In New Bedford, where ICE activity has surged, Community Economic Development Center director Corinn Williams reports clients asking how to protect assets if detained. “I get people who just bought a house and wonder what to do if something happens,” she said. “We help them create durable powers of attorney or real‑estate trusts. In one case, an ICE detainee in Texas signed a power of attorney to his son.” The tense climate makes future planning for immigrant families stressful.

Nearby, Guelmie Santiago runs Santiago Professional Services. Her 95 % Spanish‑speaking New Bedford clientele now ask about additional safeguards. Her team advises on powers of attorney, child‑care authorizations, and property protection.

Lamarche emphasizes that the rise in Latino and Hispanic home ownership reflects hard work. “To be stripped of this dream and labeled criminals is disheartening and unfortunate,” she said.