U

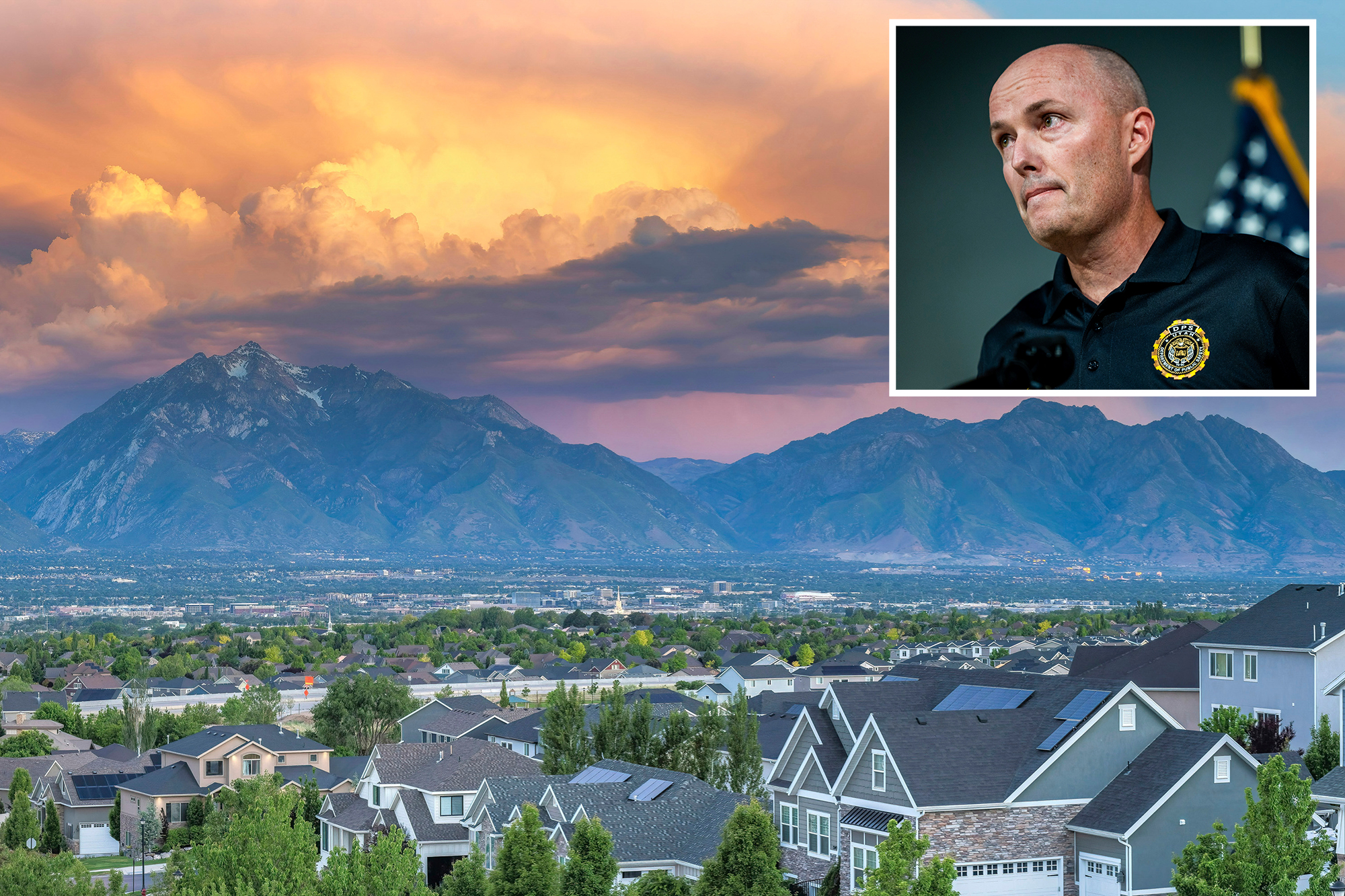

tah’s housing crisis is worsening. Median home prices are close to $600 000 and only 9 % of people who don’t own a home can afford one, according to the University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Institute. Gov. Spencer Cox has responded by proposing a bold shift: the state would take zoning authority from local governments and use its power to allow higher‑density housing across Utah.

Cox’s plan centers on statewide zoning preemption, a tool that would override city rules and enable smaller lots, duplexes, triplexes and other denser options even in municipalities that have resisted such changes. The idea is to curb the spread of low‑density, car‑dependent sprawl that drives up infrastructure costs, traffic, health risks and wildfire exposure. A 2015 study estimated that unchecked sprawl costs the U.S. nearly $1 trillion a year—about $750 per person in added roads, utilities and emergency services.

In Utah, roughly 75 % of urban land is locked into single‑family zoning, effectively banning many affordable housing types. The state is projected to be 50 000 homes short in the next decade, and the median home price is five times the median income—a level economists call “extremely unaffordable.” Cox says preemption is not his first choice, but it is on the table because local rules are stifling supply.

Supporters argue that removing regulatory barriers will let people build the types of homes that have historically grown Utah’s towns. “We’re not forcing people to do anything,” says Alli Quinlan, acting director of the Incremental Development Alliance. “We’re just removing the rules that keep them from doing it.”

Opponents, especially local GOP leaders, see the proposal as state overreach that threatens community character and local autonomy. “If you densify, you’re just adding more people into a system that’s already at capacity,” says Mike Carey, chair of the Salt Lake County GOP. They contend that market forces—interest rates, labor shortages, land costs, inflation—are the real drivers of price, not zoning alone, and that a centrally planned housing market would not solve affordability.

Data on the supply‑price relationship is mixed. In Salt Lake City, the addition of more than 8 000 new rental units led to a 0.2 % drop in rents, according to a Yardi Matrix analysis. While modest, the decline bucks the national trend of rising rents. Utah ranks 29th in the country for housing affordability and home‑building pace, and even incremental zoning changes could help close the projected 50 000‑unit gap.

The debate echoes national battles over zoning reform. California’s SB 9, which allows homeowners to split single‑family lots and build duplexes, has struggled to deliver on its promise because of high labor costs, material shortages and utility upgrade hurdles. Sacramento issued only 2 387 of the 5 700 permits needed to meet its 2029 goal, and Los Angeles is far behind its target for rebuilding after recent wildfires.

If Cox’s top‑down approach succeeds, it could become a new model for states grappling with housing shortages. If it fails, it may reinforce the reality that even aggressive reforms cannot overcome NIMBY resistance, supply‑chain bottlenecks, or entrenched local politics. The outcome will shape whether Utah can move from a sprawling, single‑family ideal to a more diverse, affordable housing landscape.