L

ouisiana homeowners are bracing for a 45 % jump in insurance costs this year, a rise that mirrors a statewide surge over the past four years and is reshaping the national housing market. Investigators Claire Brown and Mira Rojanasakul spoke with residents, policymakers and industry experts to uncover how climate‑driven premiums are eroding property values in the most disaster‑prone ZIP codes.

Sandra Rojas, 69, has lived in Lafitte, Louisiana, for five generations. After surviving Hurricane Rita in 2005 by wading out of her stilts‑raised home, she now faces an $8,312 annual premium—more than double what she paid four years ago. With home values in the area down 38 % since 2020 and for‑sale signs lining the streets, Rojas feels trapped: “They won’t insure you. No one will buy from you. You’re kind of stuck where you are.”

A new study by Benjamin Keys (Wharton) and Philip Mulder (University of Wisconsin‑Madison), released this week in the National Bureau of Economic Research, quantifies the ripple effect of soaring premiums. By analyzing over 74 million housing payments (mortgage, taxes, insurance) from 2014‑2024, the researchers found that a rapid repricing of disaster risk accounts for roughly 20 % of overall insurance increases since 2017, with construction costs adding another third. In the top 10 % of high‑risk homes, premiums have depressed market values by an average of $43,900; in the top 25 %, the hit is about $20,500.

The catalyst is a “reinsurance shock.” Global reinsurers, which help insurers limit exposure to catastrophic events, have roughly doubled the rates they charge since 2018—a response to a “climate epiphany.” This shift forces primary insurers to raise premiums, and the burden falls on homeowners. Keys notes that many residents are unaware of the heightened risk: “Homeowners don’t appreciate or don’t understand that we are living in a much riskier world than we were 25 years ago. And that risk? They have to pay for it.”

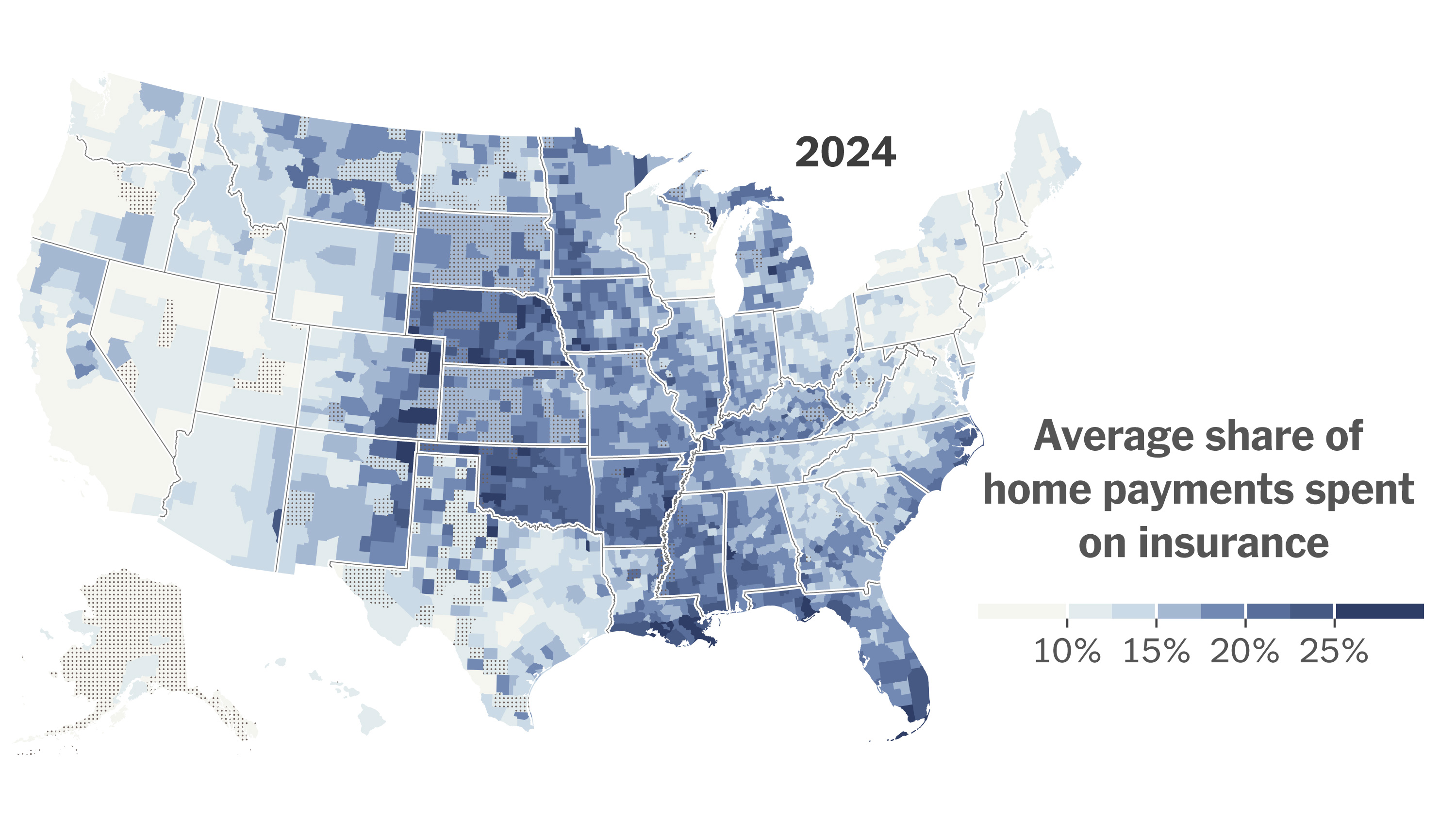

The impact is felt across the country. In the Midwest, hail‑prone regions now see insurance represent over 20 % of a homeowner’s total housing costs; Orleans Parish, Louisiana, approaches 30 %. In Bogalusa, a small inland Louisiana town, Cristal Holmes’s premium quadrupled in 2022 to $500 a month on top of a $700 mortgage. After her warehouse hours were cut from 56 to 35 a week, she fell behind on payments and feared foreclosure. Real‑estate agents report daily calls from clients who can no longer afford rising premiums, yet banks refuse mortgages without coverage, forcing owners to choose between unaffordable insurance or losing their homes.

First‑time buyers are also hit hard. Nancy Galofaro‑Cruse, a senior loan officer, estimates that over a third of prospective buyers in the region abandoned their search this year because combined insurance and interest rates pushed monthly costs beyond reach. Similar patterns emerge in Colorado, where wildfires and hail have doubled average premiums in the last decade, and in California, where 13 % of agents saw deals collapse in 2024 due to unaffordable coverage.

State regulators are taking notice. Colorado’s insurance commissioner, Michael Conway, warns that the insurance market could “decimate the real estate market” if unchecked. In California, new rules now allow insurers to pass reinsurance costs directly to consumers, a change that advocacy groups predict could raise net premiums significantly.

The financial strain extends beyond individual homeowners. As insurance costs climb, home values must adjust to keep monthly payments affordable. Lower property tax revenues could reduce local budgets for essential services or limit borrowing capacity. Clarence Guidry of Lafitte illustrates this dilemma: a $20,000 annual premium would require him to cover the first $50,000 of hurricane damage before the insurer pays. His lender insists on insurance, but the monthly cost would be 40 % higher than his mortgage and taxes combined. Guidry has withdrawn retirement savings to pay his loan and plans to self‑insure for wind and hail, joining the 13 % of U.S. homeowners who remain uninsured.

The study’s methodology relied on CoreLogic escrow data from 2014‑2024, separating mortgage and tax payments from insurance costs to calculate mean insurance shares of total housing payments. The analysis excluded utilities and homeowners’ association fees.

In summary, the rapid rise in home‑insurance premiums—driven by reinsurance rate hikes and escalating disaster risk—has already begun to depress property values in high‑risk ZIP codes. Homeowners face a stark choice: absorb unaffordable insurance or sell, while buyers confront higher entry barriers. If the trend continues, the housing market and local economies could experience significant strain, prompting regulators and policymakers to seek solutions that balance risk protection with affordability.