G

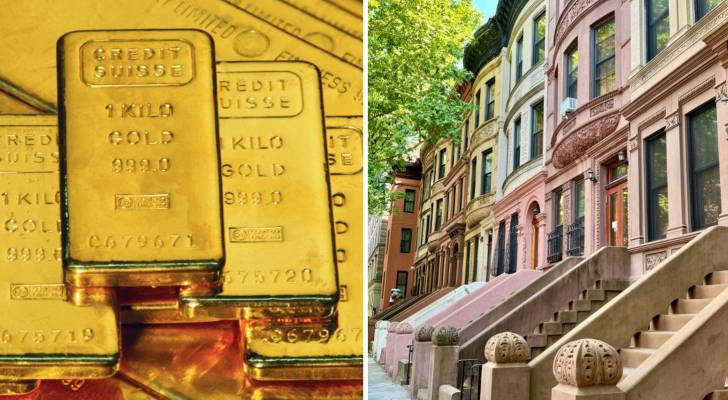

oldman Sachs compares gold to Manhattan real estate, noting that while the metal’s quantity cannot be increased, it can be transferred from one holder to another. The firm’s analysts explain that gold’s value is set by ownership changes rather than production, just as real‑estate prices shift when properties change hands. In 2025, gold broke a record at $3,700 per ounce (≈C$5,200). Manhattan’s scarcity drives its high costs: as of July 2025, the average rent for a 695‑sq‑ft apartment was $5,620 (≈C$7,865), and the median sale price hovered around $1.4 million (≈C$2 million). Both assets are constrained by supply; nearly all gold mined remains in vaults, jewelry, and central‑bank reserves, with only about 1 % of the existing 220,000‑ton stock added annually. Thus, gold’s scarcity, like Manhattan’s, is rooted in accumulation rather than consumption.

Gold’s market dynamics are shaped by two buyer categories. “Conviction buyers,” such as central banks, institutional investors, and ETFs, drive long‑term price trends. “Opportunistic buyers,” typically households in emerging markets, purchase when prices dip, providing a floor during downturns. Manhattan’s real‑estate market mirrors this structure, with institutional investors and developers acting as conviction buyers, while individual buyers and speculators play the opportunistic role.

Gold’s price reflects who is willing to hold versus who is ready to sell, not traditional supply‑and‑demand curves. As Goldman’s note emphasizes, the asset’s value is set by ownership transitions, not by a balance of production versus use.