J

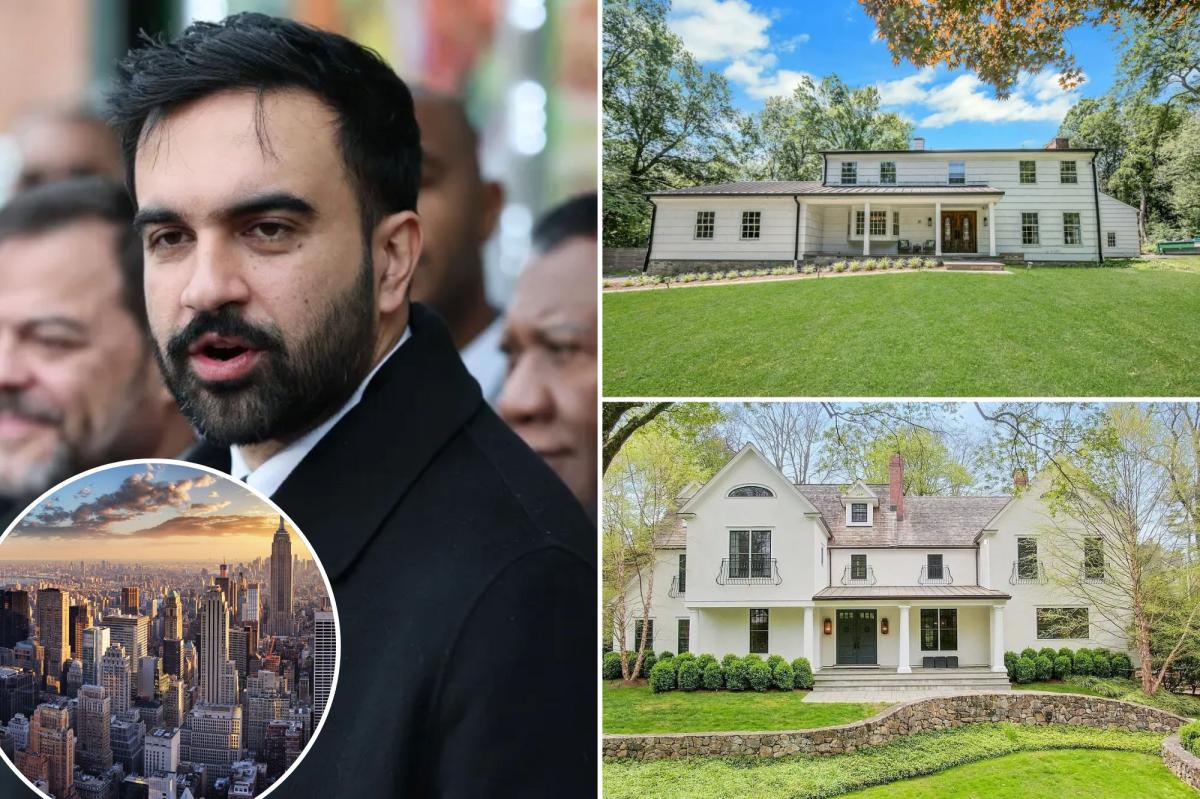

oy Metalios, a seasoned Houlihan Lawrence agent in Greenwich, Connecticut, received her first call before breakfast and five more by noon. By the day’s end, she had answered so many inquiries from New York City families that she stopped keeping count. The surge coincides with Zohran Mamdani’s rapid rise in the New York City mayoral race, prompting residents to seek refuge in the leafy suburbs of Connecticut and Westchester County. They fear that a new mayor could alter the city’s economic and social landscape, pushing them toward quieter, more affordable communities.

Suburban brokers describe the current market as a frenzy reminiscent of the early‑pandemic exodus. Properties disappear within days, driven by fierce competition and all‑cash offers that inflate prices beyond expectations. In Greenwich, a once‑abundant market now lists only about 117 homes, down from over 800 a few years ago. This scarcity fuels intense rivalries, even for multimillion‑dollar estates.

Metalios recently closed a $2.96 million all‑cash sale of a five‑bedroom colonial at 10 Old Forge Road, listed at $2.39 million in late July. The home, set on two acres with a sunlit kitchen and expansive deck, attracted ten offers. Another property, a renovated five‑bedroom at 156 Old Church Road, sold for $4.82 million in the summer—more than double its 2016 price—after an all‑cash bidding war. “We’ve seen bidding wars and people coming out of New York City,” she told The Post, citing the mayoral race as a catalyst. Her team, which closed $227 million in Fairfield County last year, has already surpassed $260 million in pending and completed transactions by the third quarter, a pace unusual for the autumn season.

Greenwich’s median sales price in September reached $2.1 million, up 11.9% year‑over‑year, though volume dipped slightly to 49 homes amid the scarcity. In Westchester, Compass’s Zach and Heather Harrison listed a four‑bedroom colonial at 21 Springdale Road in Scarsdale for $1.49 million on an October Thursday. By Sunday, the home had received more than 75 viewings and 24 bids, ultimately selling for over $700,000 above asking. The 2,638‑square‑foot property, with an open kitchen‑family room, a wood‑burning fireplace, and an oversized deck, exemplifies the spacious, family‑oriented appeal drawing city escapees. “Our open houses are the hottest ticket in town,” Zach said, comparing the traffic to a Knicks game at Madison Square Garden. Heather added that the market is even crazier than during COVID.

County‑wide data shows a 15.4% rise in single‑family contracts above $1 million from August to late October compared with the prior year, and a 225% jump for homes over $5 million, according to OneKey MLS. Showings per listing climbed 28.1% this fall versus midsummer. “Many buyers mention concerns about the mayoral election as a key driver,” Zach noted. Buyers repeatedly voice worries about rising levies, public safety, and urban livability under a Mamdani administration. “One of the great things about Westchester County is we don’t have a resident income tax in most of our towns,” he added.

In Greenwich, inventory has plummeted from over 800 homes to about 117. Douglas Elliman’s Keyan Sanai described a prospective buyer who demanded a “Mamdani discount,” fearing a post‑election drop in values. The buyer halted the search after a few days, planning to leave the city. Another developer paused a building acquisition, concerned about a potential 20% value decline. “If I buy now and this guy gets elected, it’s going to be a raw deal,” one client told Sanai. “Everyone’s either holding off or saying, ‘Let’s be out by Jan. 1, even if we sell at a loss.’”

Frances Katzen, also at Douglas Elliman, observes affluent clients reassessing portfolios amid proposals for steeper progressive taxes and expanded social programs. “People are very concerned,” she said. Some are heading to the Hamptons or beyond, unwilling to risk school environments or investment stability. “They’re going to leave the city,” she added, noting plans for universal childcare, fare‑free buses, and municipal groceries funded by hikes targeting corporations and high earners.

In Southport, Connecticut, Libby McKinney Tritschler of William Raveis reports a similar rush. Her $12 million listing at 260 Willow St.—a seven‑bedroom waterfront compound with a guest house, pool, and bespoke millwork—has generated brisk interest, far outpacing pre‑pandemic norms. The property logged four showings in three weeks, versus one every quarter previously. Meanwhile, a six‑bedroom Fairfield property at 971 Hulls Farm Road sold immediately after listing for $3.87 million, with many backup offers. It had initially listed for $3.75 million. “It’s feeling a little bit like when Covid first came about,” Tritschler said. “There’s been a lot of rumors over the last few months about the mayoral race in New York. I think there really will be a little bit of an exodus if the mayoral race goes the way they’re claiming it will.”

Tritschler added that because of the low supply of homes, New Yorkers are finding other alternatives. “I’m seeing some people even rent temporarily until they can find a home here,” she said. “That’s been a big piece of the puzzle lately.” Agents emphasize that while election jitters amplify long‑standing grievances over crime and costs, the suburbs’ allure—lower taxes, yards, and perceived security—predates the campaign. “A lot of it has to do with safety. And just not wanting to raise our kids there,” Metalios said.