S

oaring property prices are outpacing potential savings from interest rate cuts, leaving first home buyers with a hefty bill if they wait for the perfect time to enter the market. According to Aussie Home Loans modelling, a buyer who borrows in 2026 will spend an extra $77,000 over the life of their loan compared to buying now, including an additional $7,000 for their deposit.

This represents a significant cost for the estimated 100,000 first home buyers entering the Australian market annually. With housing demand outpacing supply and property prices continuing to rise, this could add up to a staggering $7.7 billion in extra costs for buyers who wait.

Since 2020, average deposits for first home purchases have nearly doubled, meaning buyers now need twice the savings and double the time to save for a 20% deposit. This is on top of individual state-based waiting tax implications.

In Western Australia, the waiting tax increases to $164,000 over the life of a loan, with buyers expected to need an additional $15,000 for the deposit on the same house by 2026. In Queensland and South Australia, the cost of waiting is more than double the national average, reaching $130,500 and $138,000 respectively.

Mortgage broker Alya Manji warns that while lower interest rates are considered good news for borrowers, they also stimulate buying activity, with house prices already trending higher for the third consecutive month. "Many first home buyers become fixated on holding out for the right price or waiting for more cuts," she said. "But in reality, the perfect time to buy was yesterday."

Manji suggests that buyers can take control of their situation by exploring alternative options such as low deposit loans, guarantor support, and lenders mortgage insurance. However, even with these options, property prices will continue to rise, and buyers need to think carefully about how much they are losing by waiting.

Homeowners in rezoned areas who refuse to sell their properties to developers may also be at risk of losing a significant amount of money. While some homeowners have scored big financial rewards by holding out for higher offers, this is not always the case. In fact, homeowner-developer stand-offs rarely pay off, and buyers can end up losing much more than just the waiting tax.

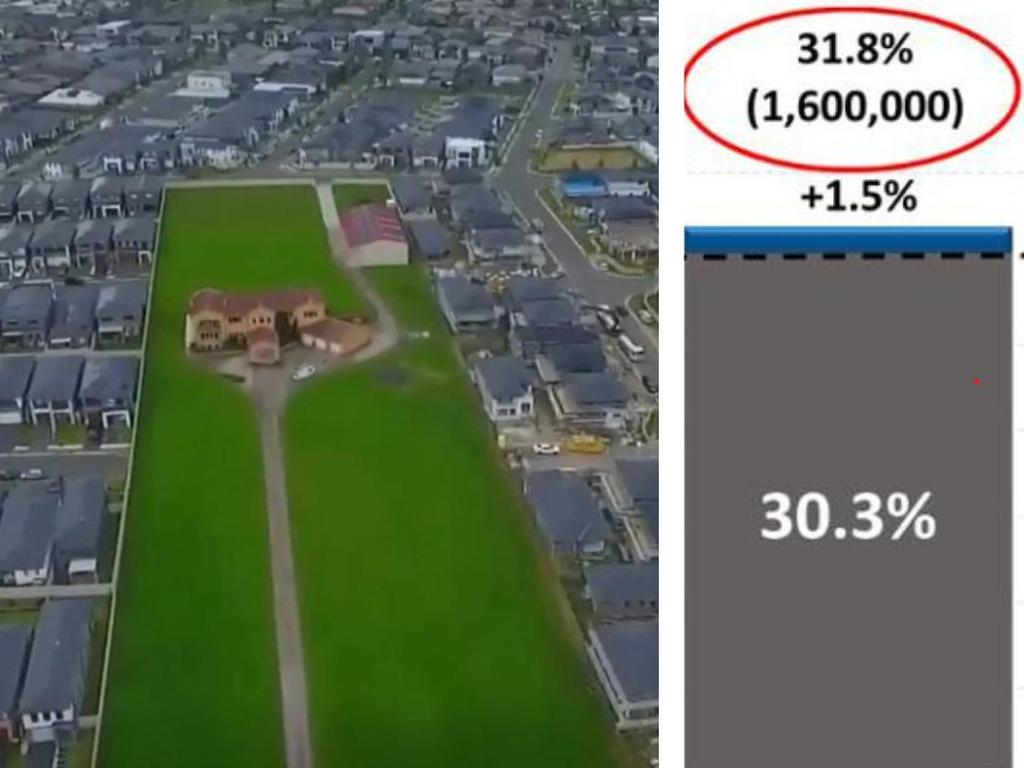

As an example, the Zammit family in northwest Sydney spent years knocking back developer offers before finally selling their 20,000 sqm parcel of land for a staggering $50-60 million. However, by this time, the property had become boxed in by new housing developments, and they could have sold it two years earlier for a better price.

Similarly, an Adelaide family that refused to sell their massive block of land for three decades finally cashed in when they sold it for $5.5 million last year – $2.2 million above its price guide. However, this was after 30 years of missed opportunities and lost money on the value of their home.

Ultimately, homeowners who refuse to sell their properties to developers may be moving backwards with the market, rather than forwards. As Manji said, "It just doesn't make sense."